Search & Discover

Story 4

Patrons

As a freelance composer—his choice—Beethoven acted as his own agent. Despite the complaints found in many of his letters, he was highly successful. Arranging his life to fit his ideals was also a paradox, an apparent contradiction.

He demanded freedom, did not respect authority, and felt equal to aristocrats. Yet he sought and accepted fees, favors, free meals, and personal friendships from exactly those who had both wealth and influence. It says a great deal about the power of his personality, boldness, and talent that Beethoven could manage his life in this way.

Some of the most notable Viennese aristocrats were his patrons.

Each prince had a palace in Vienna and estates in neighbouring countries. One was the brother of the Emperor. Some were musicians themselves. You can learn about each man by clicking or tapping on his name or picture.

Star Power

That Beethoven could command attention and a unique loyalty from those with influence is clearly seen in what happened at the end of 1808.

Beethoven was 38 and highly regarded as a virtuoso pianist, remarkable improviser, and important composer. Napoleon’s brother, Jerome Bonaparte, was the King of Westphalia, and he invited Beethoven to be the head musician in his court in Kassel, Germany. Beethoven accepted.

His Viennese patrons were surprised! They were also determined not to lose their musical “star” to another country and a much less famous city. Archduke Rudolph, Prince Lobkowitz, and Prince Kinsky jointly arranged to provide Beethoven with an annual annuity (money paid to someone, usually for the rest of their life). This means that Beethoven was paid 4,000 florins per year just to stay in Vienna!

A Duel!

Vienna was a city of pianists—over 300 at the beginning of the 19th Century, it was claimed. Pianists competing in a kind of “duel” was then a popular entertainment. It was one way for a pianist to gain fame. The pianist not only needed to play very well, but he was expected to improvise—invent the music as he played. Patrons supported individual pianists and organized competitions in their mansions and palaces.

Steibelt

Performing in Public

Theater an der Wien (Wien, [Veen], is German for Vienna) was one of the main performance halls in Beethoven’s time. It was also one of Beethoven’s favorites.

Performing in such public places was necessary in order to become well-known throughout the city. Because this hall could hold a sizable audience, it was also a place in which a performer could raise a great deal of money.

For one concert in this theater Beethoven organized a long program: His first and second symphonies, his third piano concerto, and his oratorio, Christ on the Mount of Olives. He was able to charge three times the cost of a usual ticket!

The Theater an der Wien has an interesting history.

Beethoven and Publishers

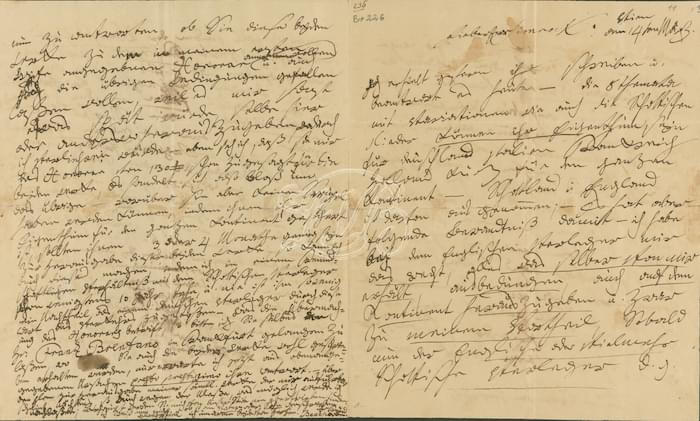

Courtesy of Beethoven-Haus Bonn, Sammlung H. C. Bodmer, HCB Br 226

Letters were the only way to communicate with those who lived any distance from you. Beethoven acted as his own agent in dealing with publishers. That meant he needed to write many letters, explaining exactly what he wanted and expected.

Nikolaus Simrock was not only one of Beethoven’s publishers, but someone he had known from his boyhood in Bonn.

He dealt with many different publishers, in different countries and

cities: Vienna, Berlin, Leipzig, London, Munich, Paris, Edinburgh. The

money Beethoven made from publishing was the largest part of his

income. This was true even if he argued with publishers that what they

sometimes offered to pay was not enough. “I enjoy an independent life

and cannot be without a small fortune and so the composer’s

remuneration must honor the artist and all he undertakes.”

In this September, 1803 letter to his Leipzig publisher, Breitkopf & Härtel, Beethoven says he’s sending his Variations on God Save the King (underlined in the letter) and his Marches for Piano Four Hands. You can hear both of these works in More Sounds of Beethoven below.

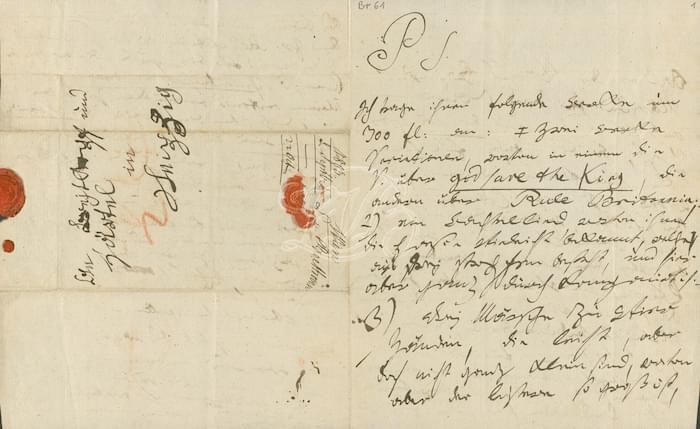

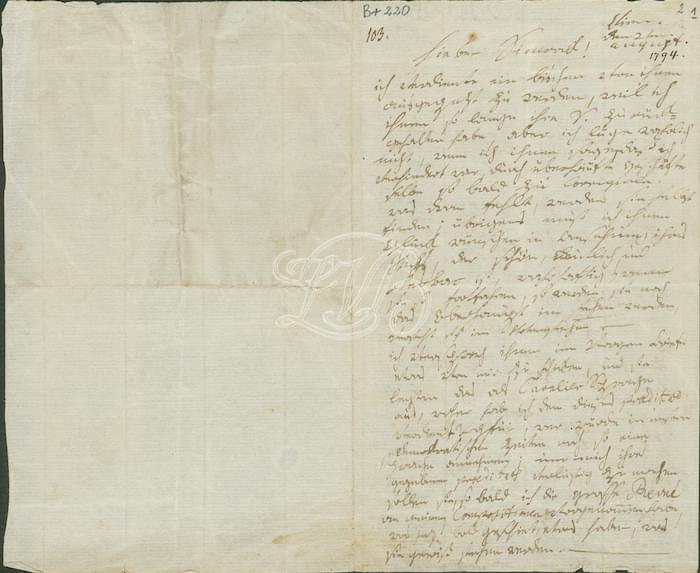

Courtesy of Beethoven-Haus Bonn, Sammlung H. C. Bodmer, HCB Br 61

Ice Cream!

The business letters sometimes contained news and casual comments. In this August, 1794 letter to Simrock Beethoven writes, “We are having very hot weather here; and the Viennese are afraid that soon they will not be able to get any more ice cream. For, as the winter was so mild, ice is scarce.”

Why were the Viennese so concerned with not having enough ice? How did they make ice cream before they had refrigeration? Reading a recipe for how ice cream was made in Beethoven’s time will explain the process.