Search & Discover

Story 8

Ode to Joy

Beethoven used Friedrich von Schiller’s poem, Ode to Joy (An die Freude) in the last movement of his Symphony No. 9. Schiller himself didn’t think this was among his great poems. But, transformed by Beethoven’s musical setting, these words and this music have become an internationally recognized call to freedom and unity.

The choral excerpt from the symphony has become a separate composition, arranged in different versions.

Schiller’s words, already changed somewhat by Beethoven himself, were further adapted to suit specific needs and situations. Conducted by Leonard Bernstein, it was performed on Christmas day after the fall of the Berlin Wall. The word “joy” (Freude) was replaced by the word “freedom” (Freiheit).

The melody was adopted as the European Anthem in 1972, meant to symbolize the European Union. In the official version there are no words; music is recognized as the universal language. Different arrangements include modified versions of Schiller’s original poem.

In Nürnberg, Germany, a flash mob comes together to perform a special arrangement of Ode to Joy. The group seems to appear spontaneously in a public space, but flash mobs are usually organized via some form of social media. The group assembles gradually, performs, and then disappears. Flash mobs are a type of performance art.

A Remarkable Premiere

The premiere performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony was in the Imperial and Royal Court Theater of Vienna, a hall that had heard premieres of works by Haydn, Mozart, and Salieri.

The Ninth Symphony was written for the largest orchestra Beethoven had ever used. It required the services of the house orchestra, The Vienna Music Society, a specially chosen group of amateurs, and four vocal soloists. The soprano soloist, Henriette Sontag, was 18, and the contralto, Caroline Unger, was only 20.

The concert was actually conducted by Michael Umlauf. Beethoven was on the stage. The performers were told to ignore Beethoven’s directions. One of the violinists later said that Beethoven “threw himself back and forth like a madman,” beating time and turning pages of the score. When the symphony ended, he was still conducting the orchestra he could not hear. That is why Caroline Unger turned Beethoven around to accept the applause. The concert was an enormous success!

A Loyal Landlord

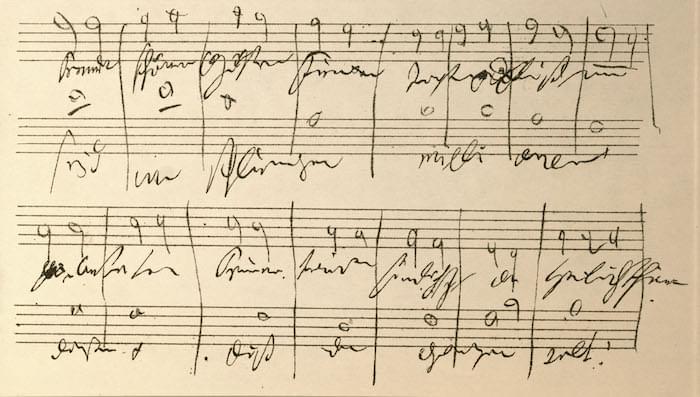

Courtesy of Beethoven-Haus Bonn, NE 81, Band II, Nr. 380

Beethoven moved frequently, sometimes every year. Most of the apartments and houses were provided by his wealthy patrons. One of the places Beethoven lived was in the Pasqualati House. The house (really a large apartment house) had been built by Empress Maria Theresa for her personal physician, Joseph Benedikt Pasqualati. His son, Baron Pasqualati, inherited the house and was a patron of Beethoven.

Beethoven lived in an apartment on the top floor for a little over 10 years. However, he lived elsewhere for part of that time twice. The fact that Pasqualati kept that apartment for Beethoven even while he wasn’t there clearly demonstrates Pasqualati’s loyalty and friendship for the composer. While living in this apartment Beethoven worked on his Fifth and Sixth Symphonies and his opera Fidelio.

It was Pasqualati who sent Beethoven the Viennese desserts and stewed cherries!

In 1815, near the end of his residence in the Pasqualati House, Beethoven sent the Baron a canon as a New Year’s Eve gift. Beethoven wished the Baron happiness—Glück—in the New Year.

Beginning of the End

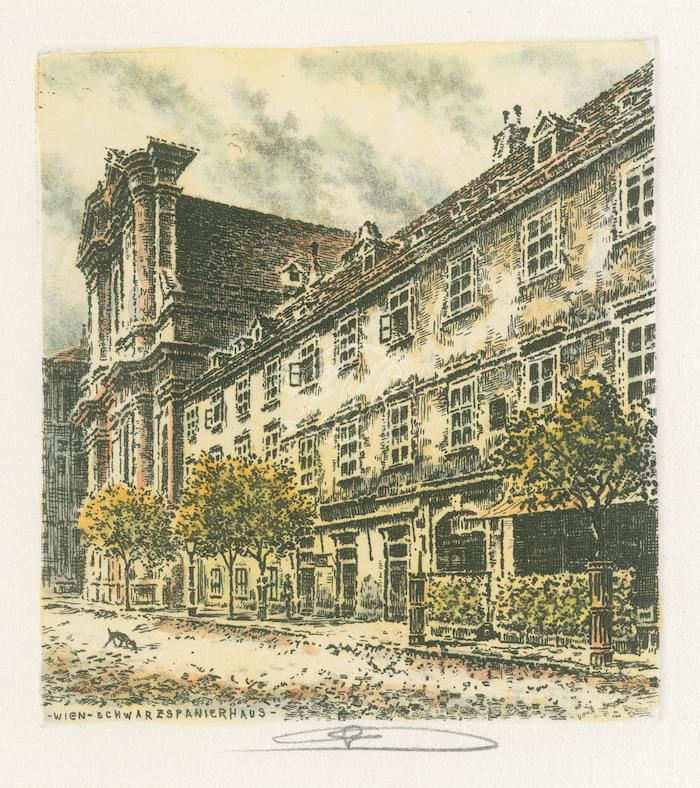

In the fall of 1825 Beethoven moved into a set of six rooms on the third floor of a building known as The Black Spaniard’s House (Schwarzspanierhaus). The building was connected to a church that was once part of a monastery of black-robed, Spanish Benedictine monks.

Stephan von Breuning, his friend from childhood, lived nearby. Beethoven often dined with the von Breuning family. Sometimes he even sent over food that he asked von Breuning’s wife to cook. Gerhard von Breuning, then 12 years old, often ran errands for him.

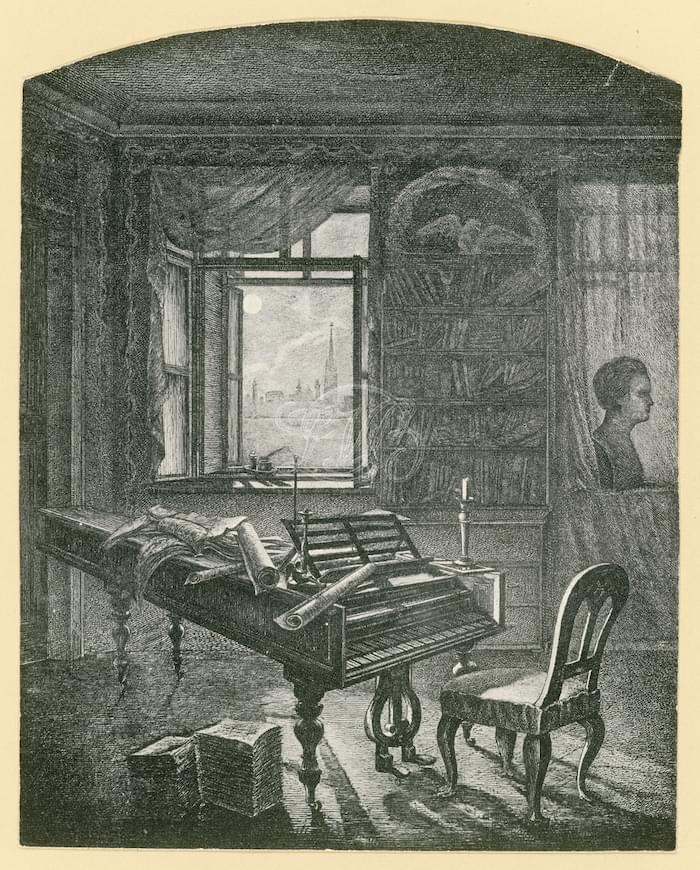

By this time Beethoven was very sick and found it difficult to eat. Yet, ever independent, he continued to drink coffee and wine and enjoy those treats (like cherries and Viennese desserts) that friends brought or sent him. He also continued to compose: string quartets, canons, and even sketches for a tenth symphony.

Courtesy of Beethoven-Haus, Bonn, B 2390/l

There were only two people present when Beethoven died. But his funeral procession was nearly a mob scene. Schools and theaters were closed. Nearly a tenth of Vienna’s population joined the long line of those who paid tribute to their own great composer.

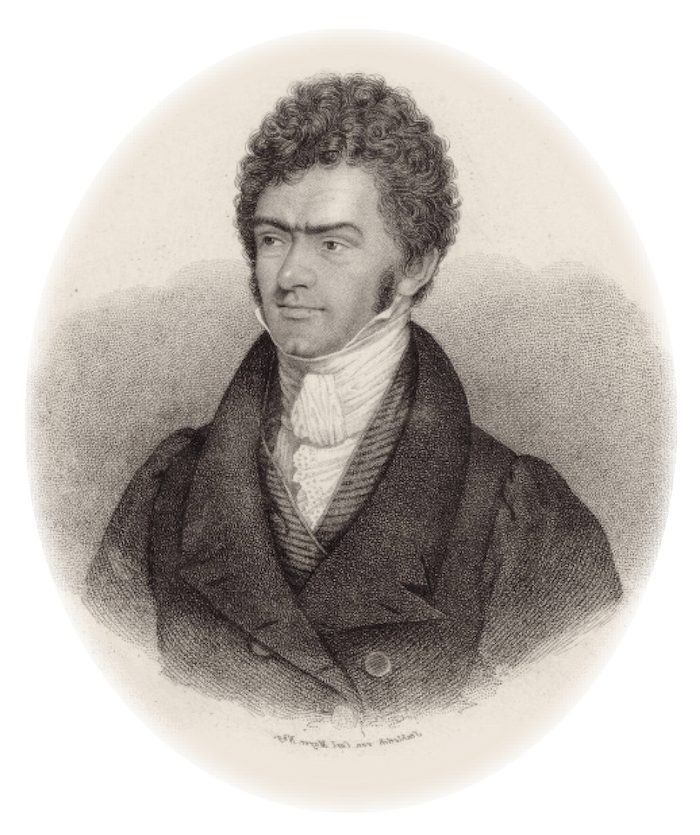

Beethoven The Legend

Millions of words have been written and spoken about this unique

genius and creative artist. He has been admired, respected, applauded,

criticized, understood, analyzed, imitated, misunderstood, and pitied.

He has been called a revolutionary, a romantic, a loner, an eccentric,

an idealist, and a grumpy bear.

Those who knew him provide vivid descriptions of their impressions

and experiences.

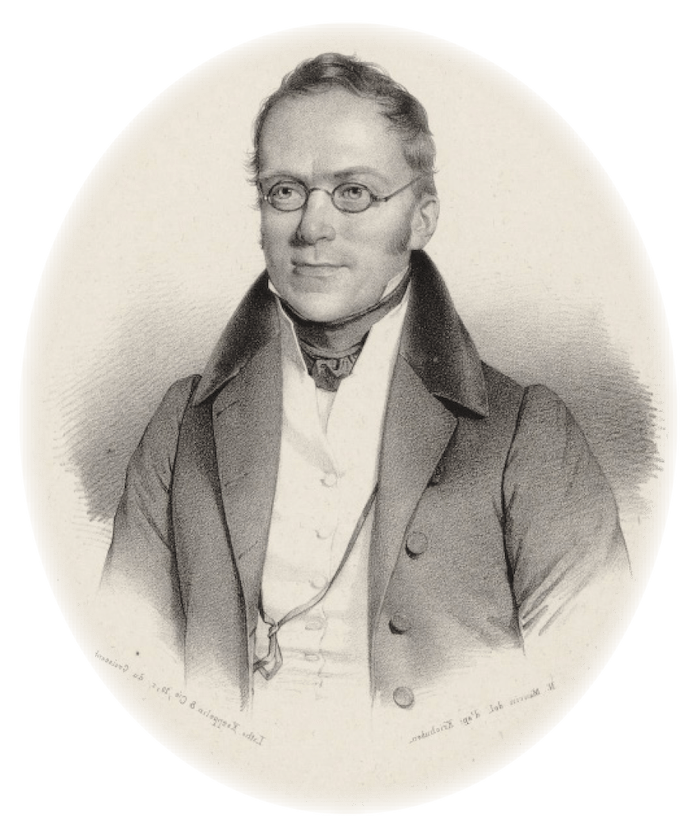

Ludwig Rellstab

German poet and music critic

He was responsible for the nickname, Moonlight Sonata.

I cast a quick glance ...

Ferdinand Ries

German pianist and composer

For several years he was Beethoven’s pupil, friend,

and secretary.

Beethoven had studied violin with Ries’s father, Franz Anton

Ries, in Bonn.

Beethoven was very clumsy ...

Carl Czerny

Austrian pianist, teacher, composer

He was Beethoven’s pupil and, later, friend. He could play all

of Beethoven’s piano music by memory.

Czerny was 11 when his father took him to play an audition

for Beethoven.

I had to play something ...

Johann Andreas Stumpff

Piano and harp manufacturer

Although he was born in Thuringia, he spent most of his life

in London.

He visited Beethoven in Vienna in 1824.

Now the table, ...

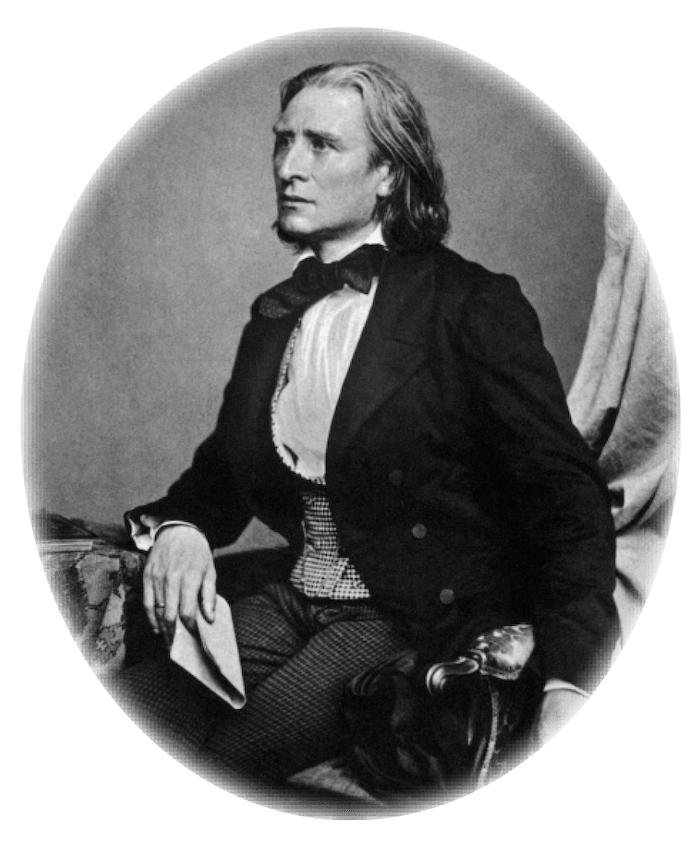

Franz Liszt

Hungarian pianist, composer, and teacher

Carl Czerny, who was then his teacher, brought Liszt to play for

Beethoven when Liszt was 11 years old.

The first thing I played ...

Each personal remembrance of Beethoven, however revealing, is only a

selective snapshot of a unique, complicated, and

temperamental man.

Beethoven was always direct, plainly honest, sharp, and often blunt.

He said what he meant.

It’s best, therefore, to let him speak for himself.

love virtue and all that is fine and good.

Music comes to me more

readily than words.

I would rather write 10,000 notes than a

single letter of the alphabet.

Tones sound, and roar and storm

about me until at last they stand before me

in the form of notes.

Music is like a dream.

One that I cannot hear.

I love a tree more than a man.

I love the truth more than anything.

I live only in my scores, and when

one thing is hardly completed,

another is already on the way.

To play a wrong note is insignificant;

to play without passion is inexcusable!

Beethoven can write music, thank God,

but he can do nothing else at all.

Nothing is more intolerable

than to have to admit to yourself

your own errors.

My heart is good.

I am fond of an independent life.

Write to us at faber@pianoadventures.com